Hundreds of people have asked me about Soylent, a controversial Silicon Valley team trying to replace food with a grayish liquid.

“Does it really deliver all the nutrients the human body needs?”

“Is it safe?”

“Why hasn’t anyone tried this before?” [Hint: they have]

And most often: “What do you think of Soylent?”

Serendipitously, four or so weeks ago, I received an e-mail from Shane Snow, a frequent contributor to Wired and Fast Company:

I’m sure you have seen the buzz about the food-hacking movement, where a couple of Silicon Valley techies have been creating Matrix-style food replacement formulas for “optimum” chemical nutrition. Soylent.me, in particular, has been buzzing like crazy, having raised $800k in a Kickstarter-like campaign.

But nobody (besides the creators) has gotten his or her hands on any yet.

Except me.

Naturally, we had to do an experiment.

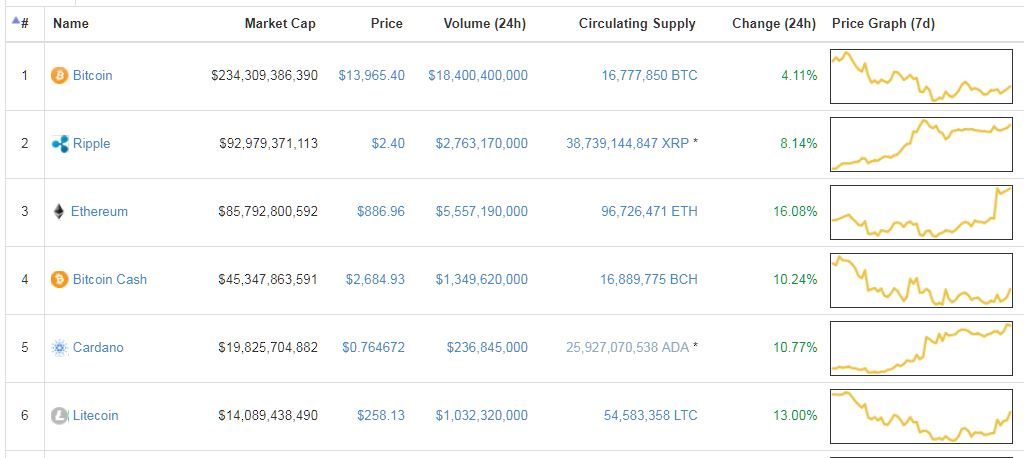

This post describes the longest non-employee trial of Soylent to date (two weeks without food), including before-and-after data such as:

- Comprehensive blood panels

- Body weight and bodyfat percentage

- Cognitive performance

- Resting heart rate

- Galvanic skin response

- Sleep

I share my thoughts in the AFTERWORD and occasionally in brackets, but this article focuses on Shane’s experience and data. Please also note that this is *not* a Soylent take-down piece. I hope they succeed.

That said, there are some issues. I expect the debate on Soylent to be fierce, so please leave your thoughts in the comments. I’ll encourage the Soylent founders to answer as many questions as they can. From all sides, I’m most interested in studies or historical precedent that can be cited, but logical arguments are fine.

Enjoy the fireworks…

Enter Shane

It’s seven a.m. on a Wednesday, and I am in my kitchen staring at a bag of flour. A crinkly, metallic bag with a blue, Superman-style “S” logo glued to it. With no scissors handy in my one-bedroom Manhattan apartment, I’ve managed to tear the bag open roughly with my teeth, inhaling a blend of oatey sawdust that, when mixed with water, will be my sustenance for the next two weeks.

I stare at it, thinking about all the pizza I won’t be eating, and the donuts Rebecca from the office will surely set out on the table next to my desk. But, I had all those things last night as a parting gift to my taste buds, so I sigh, pour the flour mix into a 2-litre pitcher of cold water, and shake.

Bottoms up.

This is Soylent. Not the cannibalistic “Soylent Green” that Charlton Heston weeps about in the 1970s sci-fi movie, nor the soy and lentil “soylent” steaks in Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel, Make Room! Make Room!. This is Soylent, the tasteless, odorless food replacement drink that a kid in California—who raised a million bucks from strangers like me—invented to take food out of our daily equation and, ambitiously, cure world hunger. This is the Soylent that geeks in Silicon Valley have been buzzing about for the better part of a year, and the Soylent that various nutritionists have attacked with dire arguments of Ad Hominem mixed with Appeal to Authority. This is the Soylent whose inventor, Rob Rhinehart claims has made him fitter, more alert, and more productive, after having drank it semi-exclusively for about seven months.

… and it tastes like oatmeal water. Not bad, I admit as I gulp down half a Nalgene bottle’s worth for my first of many non-breakfasts with the stuff. I fill a second Nalgene to drink after work, and leave the Fedex box with a dozen more crinkly bags on the kitchen counter as I lock the apartment door behind me.

On the surface, Rhinehart, a 24-year-old entrepreneur and engineer, seems an unlikely person to invent such a concoction. I had reached out to him months ago after reading his blog, where he moaned about how time consuming cooking and eating food is for him, and documented the development of a meal replacement in the vein of the amino acid goop served on board The Nebuchadnezzar in The Matrix. But when we met up a few weeks ago in Brooklyn, Rhinehart became in my mind the most likely person to invent such a drink. Quiet, earnest, with the precise diction of someone smarter than any of your friends (unless you hang out at science poetry slams), Rhinehart strikes you as the kind of obsessive introvert who really doesn’t have the patience for food and just might be willing to cram a decade of biology and chemistry into his head during Winter Break to invent a cure for it.

Basically, he’s a hacker. He’s just taking that hacker’s mindset to the human body.

“People see some credential as this binary thing,” he explained to me about why he’s qualified to do this. “The formal path is really inefficient.” But by devouring textbooks and seeking mentorship from master chemists and nutritionists, and bringing his experience in electronics manufacturing (which turns out to be strangely analogous to mass-producing supplements), he had successfully reverse-engineered—at a molecular level—exactly what the human body needs out of food. He claimed, at least.

And that’s where the nutritionists and whole foodies start to freak out. As Rhinehart published his findings and geared up to take his chemical smoothie to market (the natural thing for a Silicon Valley-ite to do upon inventing anything), the objections started to chunkily pour in like mineral-packed oat-water in a Nalgene bottle. The most common include the following:

- The body needs whole foods and not atomic nutrients; the synergy between diverse ingredients is what matters in nutritional uptake.

- We don’t know what we don’t know about nutrition (i.e. Soylent might be unexpectedly harmful).

- The inventor has zero background in health.

- Some of its core ingredients are nutritionally empty.

- “If food is too hard, you’re doing it wrong.”

- It’s “ludicrous” and “dangerously unhealthy.”

- It hasn’t been scientifically tested by anyone but the founder.

I love food as much as the next person. As a New Yorker, I hang out with whole foodies, juicers, raw vegans, and holistic health coaches aplenty. As a vegetarian, I am no stranger to dire warnings about dietary choices, or superstitions many people have about food. But as a technologist, I can relate to Rhinehart’s questioning of the assumptions we perceive as granted. (For example, I’m nervous about antioxidants, as some studies indicate they’re harmful to the point of causing cancer; however, most of us assume “high in antioxidants” is a selling point.)

So, when I look at the above list of objections, I think this:

- The body needs whole foods, not atomic nutrients; the synergy between diverse ingredients is what matters in nutritional uptake. This sounds nice, but has not been scientifically proven.

- We don’t know what we don’t know about nutrition (i.e. Soylent might be unexpectedly harmful). That’s not a good reason to not try to innovate. Why not do some tests?

- The inventor has zero background in health. If we’re going to dabble in logical fallacies, this one is better: If a man with a bachelor’s degree can invent self-landing rockets, then a kid with the same degree and a blender can invent a meal replacement drink.

- Some of its core ingredients are nutritionally empty. The Soylent team claims they’re updating the formula to resolve such concerns. But even so, is Soylent on the whole less healthy than the average person’s diet? Are the “filler” ingredients supplemented in a way that delivers balanced nutrition? Those are the questions that need answering.

- “If food is too hard, you’re doing it wrong.” Given the obesity epidemic in America and the number of malnourished people in the world (including America), it’s not a stretch to say food is indeed hard for a whole lot of people.

- It’s “ludicrous” and “dangerously unhealthy.” Given the lack up scientific backup for such statements, this is only conjecture at this point.

(Interesting side note: Rhinehart told me that Soylent meets FDA guidelines; the crowdfunding campaign says the components are FDA approved, and Soylent will be made with “strict regulatory controls.” I’m curious what those controls are, but it sounds to me like he is essentially cooking with FDA approved ingredients but hasn’t gone through the nightmare that is the FDA testing process on the final product yet. Not that FDA approval means something is perfectly safe for all people, per se.)

- It hasn’t been scientifically tested by anyone but the founder. I want to test it.

As the crowdfunding orders piled up, and it became clear that Soylent’s delivery would be delayed like every Kickstarter project ever funded, I asked Rhinehart if I might get my hands on some supply, so I could do a gruel-based version of Supersize Me and measure the results of what Soylent does to a mildly out of shape 28-year-old.

He shipped me two weeks’ worth.

Then, I asked Tim Ferriss, himself a body hacker whose penchant for lateral thinking is refreshing in the echo chamber of interest-conflicted health bloggers and naysayers, for advice on how to make my two-week study scientific. He had a company called Basis overnight me a health tracking wristband, gave some advice regarding blood tests, and said, “Keep me posted!”

Now, I knew that two weeks was probably not enough time to see dramatic changes, but it is enough time, worst-case scenario, to do some damage. (However, total meltdown didn’t seem likely.) What I wanted to do was begin testing the conclusions that Rhinehart and his company had claimed, that compared to the average person’s diet…

- Soylent provides all the energy and nutrients the body needs.

- The body can absorb all the nutrients Soylent provides.

- Soylent makes one more alert.

- Soylent can help people cut fat and maintain good body weight.

- Soylent saves time and money.

- And at the end of the day: Soylent isn’t dangerous.

I consider myself a pretty health-conscious person. No alcohol. No meat. Slow-carbs when possible. Run three miles, three times a week. Pull-ups, push-ups on the days I don’t run. On the weekends, however, my weaknesses come out: I tend to devour pizza and shotgun Vanilla Coke. Despite what is probably an above-average-health routine, I am out of shape compared to five years ago when I lived in Hawaii and surfed/body-boarded every day, and I’m certain that I don’t get all the vitamins and nutrients I need—especially things like Omega-3s that vegetarians have a tough time eeking out of spinach and arugula smoothies.

Here’s what a typical day’s worth of food looks like for me:

Breakfast = Muscle Milk (often I’ll also have mate tea when I first get up)

Lunch = Chipotle vegetarian burrito (or something akin to it) and a Diet Coke

Dinner = Take out, usually something like Thai red curry with tofu

Snack = Typically, a handful or two of peanut M&Ms from the office; almonds if I’m lucky

Nutrition Facts–Grand Total:

Calories: 1862

Total Fat: 74.1g

Saturated Fat: 24.5g

Trans Fat: 0

Cholesterol: 19mg

Sodium: 4,277mg

Potassium: 1,395mg

Carbohydrates: 199.5g

Dietary Fiber: 34g

Sugars: 45g

Protein: 88g

Vitamin A: 96%

Vitamin C: 139%

Calcium: 105%

Iron: 84%

Vitamin D: 35%

Thiamin: 35%

Niacin: 35%

Folate: 35%

Biotin: 35%

Phosphorus: 35%

Magnesium: 35%

Copper: 35%

Vitamin E: 35%

Riboflavin: 35%

Vitamin B6: 35%

Vitamin B12: 35%

Pantothenic Acid: 35%

Iodine: 35%

Zinc: 35%

Chromium: 35%

Want to see the individual nutrition facts for each item? Here they are:

Muscle Milk Diet Coke Chipotle Burrito Thai Red Curry (x2 servings) Rice Peanut M&Ms

Total Cost:

$24 / day

For two weeks, I traded that in for this:

Ingredients:

(Click to enlarge. Note that my shipment had two weeks’s supply, though this paper says one.)

Nutrition Facts:

Soylent isn’t supplying a finalized nutrition facts list until the company launches this Fall, but here’s the breakdown based on information Rhinehart shared with me and has posted online, based on daily nutrition percentages for an adult male and the recommended daily serving size of Soylent. (Download his most recent nutrition facts sheet here.)

Calories: 2404

Total Fat: 65g

Saturated Fat: 95% of daily recommended value

Trans Fat: 0

Cholesterol: 0

Sodium: 2.4g

Potassium: 3.5g

Carbohydrates: 400g

Dietary Fiber: 40g

Sugars: ?

Protein: 80g (Note that early reports declared that Soylent had 50g of protein; Rhinehart recently revised his blog to say 120g of protein now, though he told me it was 80g in the Soylent Version 0.8 that I drank. The formula isn’t final yet.)

Vitamin A: 100%

Vitamin C: 100%

Calcium: 100%

Iron: 100%

Vitamin D: 100%

Thiamin: 100%

Niacin: 100+%

Folate: 100%

Biotin: 100%

Phosphorus: 140%

Magnesium: 112%

Copper: 100%

Vitamin E: 100%

Riboflavin: 100%

Vitamin B6: 100%

Vitamin B12: 100%

Pantothenic Acid: 100%

Iodine: 100%

Zinc: 100%

Chromium: 100%

Cost:

$9 / day (at the crowdfunding campaign price)

Observations

Day 0

The day before Soylent, I went in to my doctor for some fasting blood tests. Tim recommended a comprehensive swath of exams via WellnessFX, a company that collects and visualizes health information in cool, newfangled ways. Unfortunately, the nearest clinic was two states away from me. Most of the tests in WellnessFX’s “Cadillac” suite don’t have to do with dietary changes (according to my doctor), but were just plain cool and important to know about in general. So I did the next best thing and got a few panels—ones that a local nutritionist recommended—at my doctor’s office and had them shipped to a lab that WellnessFX uses. (Also note: if I had gotten the comprehensive suite here in New York, it would have cost over $5,000 to cobble together the individual tests on my own! One day, I will spring for that, but not today.)

[TIM: I disagree with Shane's doc and would argue that most blood markers can be moved up or down by diet. After all, outside of physical environments/pollutants, what other primary epigenetic inputs have greater global effects? From liver enzymes to gene expression, you are what you eat.]

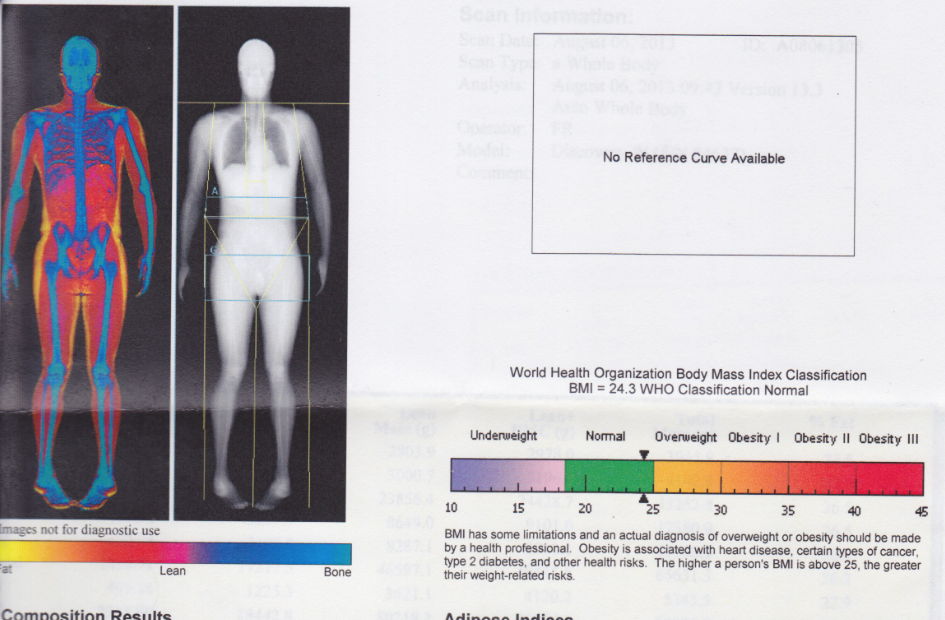

Then, I attempted to do 3 different body composition and weight tests: my FitBit home scale, a bioelectrical impedance body composition analyzer (or BIA, for which I used an InBody 230 at a local gym), and a DEXA scan at a local radiology lab. Bad news struck once again, as the DEXA scanner table was broken, “but will be fixed in two weeks.” After calling the only place in NYC that I could find that has a Bod Pod (Brooklyn College) and getting voice mail every day for a week, I decided to bag the third body scan. It was the before/after comparison that mattered anyway, which I would get with the other two just fine.

Finally, I took some tests on Quantified-Mind.com to measure my mental alertness while I was eating my typical diet of burritos and Diet Wild Cherry Pepsi. In this way, I could try to reproduce Rhinehart’s claim that Soylent improves mental acuity.

I normally wear a Jawbone UP bracelet to measure my steps and sleep, but Tim recommended the Basis band, which measures those things plus skin temperature and heart rate, so I started wearing that.

I was determined to eliminate any other variables, including bedtime, stress, and exercise, so I tried to stick to my regular routines before, during, and after the trial, and I did my best to standardize my sleep schedule and the times I weighed and measured myself, for both mind and body tests.

And then I had a mini party for myself, gorged on all the foods I shouldn’t eat, and went to bed with food in my belly for the last time.

Days 1-3

(Me. 7am. Looking like some sort of a wild animal.)

My first surprise was that Soylent tasted fine, familiar even. It’s easy to gulp down quickly. In fact, as someone who’s used to drinking disgusting vegan protein shakes made out of peas and hemp, I found it quite pleasant.

On the first day, I was struck with a wave of exhaustion around 3:30, and I had a “tired headache” the rest of the afternoon. This low energy in the afternoon is common for me, but felt particularly bad this day. I blamed it on the Vanilla Coke at 11pm the night before.

Months ago, my doctor had told me I had a mild amount of acid reflux. It hadn’t bothered me lately. But as soon as I started the Soylent, I noticed that the back of my throat started feeling like fire.

On the second day, it was clear to me that I was psyching myself out on the “no food” thing. My nose seemed to pick up the scent of food everywhere. I even wrote this in my journal:

“Last night I had a dream that I ate a brownie, and halfway through the brownie realized that I was only supposed to be eating Soylent for the next two weeks.”

By the end of Day 3 I realized that if I drank more Soylent in the morning and rationed it less, I had great energy levels in the afternoon. On Days 1 and 2, I drank about half of my supply by 8pm when I got home, and on the days that I tried to drink 3/4 of my supply by mid-afternoon, I felt great.

But also by the end of Day 3, I had a monster canker sore on my bottom lip.

Days 4-6

(Me. 7am. Still looking haggard.)

By the fourth day of Soylent, I turned a corner. I started feeling noticeably great. I didn’t get the afternoon doldrums, I wasn’t starving, and had plenty of energy for my regular, 3-mile run along the West Side of Manhattan. On Sunday, I held a marathon writing session, where I didn’t even look up for over 6 hours—a shocking feat for me lately. And my burning reflux throat was completely gone. Though the canker sore was still going strong.

WARNING: Skip to the next section if you don’t like reading about poop.

It was around this time that something I should have anticipated—but hadn’t—finally happened. My poop became Soylent. Typically (and forgive me if this is TMI) I have a bowel movement once a day; it’s rare that I don’t. With Soylent, I started going every two days. And by the time everything from before made it out of my system, said infrequent bowel movements became extremely sticky and, ahem… off-whitish-tan. It was gross, but felt strangely… purifying?

Days 7-9

(Me. 7am. Look who took a shower!)

I stopped craving food at this point. I felt fantastic. I sat at a work outing and didn’t care that I wasn’t eating the delicious guacamole that everyone was passing around. I would watch people leave for lunch breaks and chortle to myself while I got an hour of extra work done and sipped my Soylent. My energy levels were higher than I had felt in a while. I didn’t feel that sort of shaky invincible like you do after drinking a Red Bull, but I felt pretty darn close to it.

But on Day 8, something peculiar happened. I got really bad vertigo in the afternoon. Then again the next afternoon.

I soon realized this was because I had been cheating since Day 7.

What happened was my blender broke. I had been shaking and stirring Soylent by hand, which meant I wasn’t able to get all the clumps out. By this time (and either it was my batch settling or me starting to get lazy at stirring), the chunks in my mixtures were getting huge. The white stuff that was mixed into the tan stuff was floating to the top and congealing together. For the last few days, I’d tried swallowing the white chunks down and gagged on them. So I just started just scooping them out.

I’m pretty sure the white chunks were the rice protein, and perhaps something else important. Whatever it was was causing my blood sugar to crash. On the afternoon of Day 9, I bought a Magic Bullet.

Days 10-13

(Hey, look at you, Mr. Morning Person!)

The Magic Bullet did the trick. I fully mixed and fully drank my Soylent, and soon felt great. No more vertigo. Energy levels still at an all time high.

At this point, I was becoming hyper productive—both because I felt like it and because I was no longer using food as a procrastination method in my life. One of my coworkers told me I was more wired and chipper than he’d ever seen me.

[TIM: The "food as procrastination technique" is a non-trivial point. It's critical to always ask yourself: "What else could explain this effect?" Personally, I love to delay writing by snacking and drinking when totally unnecessary. If Soylent removes these delay tactics, is the improvement due to biochemical change or a behavioral change?]

Also by this time, the canker sore was completely gone (I am told it was stress), and there was still no more sign of the reflux (perhaps also stress?).

I was happy. Life was starting to feel simple. I felt… lighter… inside. Which is a hard thing to objectively measure, but that was the case.

And by the final day, to my surprise, I found myself wishing I had two more weeks’ of Soylent left.

Aftermath

My first day back to real food was a bit of a doozy. I took all the blood tests and body scans in the morning, fasting, and then went straight to upstate New York for a meeting. In the meeting, we were served pasta salad and melty cheese sandwiches, which I promptly devoured. And then felt like a camel had kicked me in the intestines. Later that day, I ate half of a pizza from Angelo’s in Midtown (great place, btw) and washed down some vitamins with Muscle Milk to ensure some modicum of nutrition.

And the next day I felt gross.

Inspired by my experience with Soylent, and with that junk food binge over and done, I committed to eating healthier on my own. And I have. I cut soda out of my diet entirely—an easy thing to do after two weeks off. After a couple days of mild indulgence on things like bread and chocolate, I’ve now restarted Tim’s Slow-Carb Diet™, this time with what appears to be a little more will power. I even started working out with a trainer. (No more half-hearted pull-ups!)

Though I felt a noticeable difference in energy after the first couple of days, once I started eating healthy on my own, I feel like I’m somewhere between my “normal” and “Soylent” level. Which is not too shabby.

(Oh, and it took two days for poop to not be Soylent anymore; four to completely return to normal. Hooray.)

Data

Here’s the raw data from my tests, plus explanations when needed:

Weight / Body Composition:

This is the embarrassing part where everyone gets to see how out of shape I am. (Note to any lazy future news reporters who arrive at this page via Google or some other future search engine: Do not describe me as 160 lbs and made of 20% fat in any future articles. I’ll soon be a changed man, I swear!)

InBody 230 (BIA) Scan, BEFORE:

(enlarge)

InBody 230 Scan, AFTER:

(Enlarge)

The BIA indicates that I lost 7.7 lbs in these two weeks. (Awesome!) Concerningly, I seemed to have lost 3 lbs of fat and 4.7 lbs of lean mass. (Hmm….)

Fortunately, only 1.2 lbs of that lean mass was “dry lean mass” aka muscle. The rest was apparently water weight. So I had a 3:1 fat loss to muscle loss ratio, which is much less concerning.

My home scale tells the same story, just scaled down about 5 lbs:

FitBit WiFi Scale, BEFORE:

FitBit WiFi Scale, AFTER:

I’m not quite so heavy on the home scale; that’s undoubtedly because the bio-electrical scanner scans you while you’re still wearing your clothes, and I was wearing pretty heavy jeans the first time I went in. To make sure clothes weren’t a factor, I wore the same jeans when I went back in the second time (both times I wore a V-neck t-shirt of similar weight).

For anyone who’s curious, I do have DEXA scans, which the place with the broken table (Chelsea Diagnostic in Manhattan) took of me on the last day of Soylent. They pretty much corroborate the %s. Here’s a fun picture:

Blood Panels:

I had several blood panels tested before and after, with the following results:

Bloodwork BEFORE:

(Click either of the below images to enlarge)

Bloodwork AFTER:

(Click either of the below images to enlarge)

You can pore through the data yourselves, but the areas that stick out to me are the following:

- Fasting Glucose went down

- Sodium and Potassium and Chloride and Carbon Dioxide and Nitrogen and Calcium stayed relatively the same

- Creatinine went up 30%

- Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate dropped 27%

- Total Cholesterol went from 127 to 117, dipping just below the normal range. (Says the nurse at my doctor’s office, “The abnormal result was your total cholesterol level which was 117mg/dL. The low limit is 25mg/dL, so it was only slightly out of range. When your levels are high this is a concern, but low cholesterol is not anything to worry about.”)

- HDL Cholesterol (the good kind) stayed basically the same

- LDL Cholesterol (the bad kind) went down from 66 to 63

- “Non HDL” Cholesterol (I assume more of the bad kind) went from 82 to 73

- Triglycerides, or fat in the blood stream, dropped 46% (apparently lowering my risk of heart disease)

- Monocytes, Absolute went up 25%

- Eosinophils, Absolute went down 33%

- Basophils, Absolute went up 25%

Mental Alertness:

I tested my reaction times via a site called Quantified-Mind early on and toward the end of my Soylent trial (and attempting to get the same amount of sleep before each test, also mitigating other variables such as mood or time of day). The site puts you through a battery of tests, randomized in groups of 7, so the results below are a combination of a couple of trials that I did in order to get matching tests both times.

(Enlarge)

Higher scores mean better reaction times and accuracty. As you can see, I improved across the board. This seems to corroborate the observation that I was feeling more alert and mentally snappy.

Vital Signs & Steps:

I wore a Basis band for the duration of the trial (with the exception of Day 5, when the battery ran out, and I left it at home charging). Below are some screenshots of early days on Soylent versus later days on Soylent.

(click either of the below to enlarge)

(Key: Blue line is skin temperature; red line is heart rate; orange bars are steps walked or run. Gaps are when I took the thing off for some reason.)

It’s difficult to pick out many Soylent-related insights from these charts, other than nothing crazy went on with my heart or skin temp throughout the trial. One interesting tidbit is my sleeping heart rate seemed to smooth out the longer I was on Soylent. There was less jumping up from 45 to 53 beats per minute and back.

I asked Bharat Vasan, one of the founders of Basis, to take a look at the limited data set I collected and help me unpack what happened. He dumped my data into a spreadsheet (which you can view in its entirety here), and commented on the following highlights:

- RHR: Your Resting Heart Rate had declined over the last 3 days of data from 50bpm to 46bpm which could be a sign of improved fitness. There are also other factors that could have contributed to it from your diet or sleep patterns. It may be interesting to chart your weight against resting heart rate.

- Sleep: You slept a little over 8 hours a night (both average and median) which is the great since that’s what’s recommended. Sleep times seem to have been pretty consistent with a couple of late nights (judging from the patterns chart below).

(Side note: one of the cool things the Basis tracks is perspiration vs heart rate. Notice with this chart how my perspiration spiked even at times when my heart rate was normal. ”Potentially due to an emotional reaction or temperature changes,” Bharat tells me. Does that have to do with diet? I’m not sure. But it’s interesting.)

Cost:

Regular diet (not including meals out with friends on weekends, which almost always includes dinner Friday night and brunch Saturday): $24/day

Soylent diet: $9/day

Savings: $15/day or $105/week ($5,460/year)

(If you include $80/weekend I typically spend on eating out here in New York, then that’s another $4,160/year, for a total of $9,620.)

Potential weaknesses in the data:

Although I attempted to eliminate variables that could affect any of my before/after measurements (such as wearing the same clothes for the bioelectrical impedance scan and taking photos and tests at about the same times of day), the following things could have affected the final data:

1) I took my second BIA approximately 3 hours earlier in the day than the first one. Though I drank tons of water during Soylent, according to the instructions, those missing 4 lbs of water weight indicate I may have been less hydrated when I came in the second time. And studies of BIA measurement (on obese subjects, at least) indicate that hydration potentially alters the accuracy of BIA muscle and fat measurement.

2) On that note: I drank more water during my 2 weeks of Soylent than I normally do. How much of my results could be attributed to that change versus the actual Soylent ingredients, I’m not sure. But it could be a factor.

3) An alternative explanation to my improved scores on Quantified Mind could be that I simply got better at the tests because I had taken them before.

4) This experiment only looks at the effects of addition (I added Soylent). The gaping hole is that I couldn’t properly test the effects of subtraction of elements of my regular diet. What if the elimination of diet caffeinated soda is what really caused the fat loss? What if Muscle Milk was making me sluggish, rather than Soylent making me alert? (I think these explanations are probably unlikely, but I’d rather be certain than hunch-driven.)

5) Perhaps most importantly with a one-man experiment like this, I’m not immune to the possibility of a placebo effect. Would I have had similar results if someone told me that a pizza-only diet would make me skinnier and snappier? (P.S. If that diet ever becomes a thing, count me in.)

What I would do differently next time:

I believe a 30- or 60-day Soylent trial would produce more conclusive (and perhaps dramatic) results than the two weeks. Before embarking on such a trial, I would test (or study) the elimination of various elements of my diet, one by one, to account for the effects of subtraction on all of the measurements I took.

Second, I would like to test Soylent with a number of subjects, and give half of them placebos. The difficulty here, of course, is in the details, and in the possibility of really screwing the placebo people over. (Do you give them a drink that truly is nutritionally empty and then watch them nearly starve to death? What do you split test: high carbs and low carbs, high vitamins and low vitamins, individual ingredients? Do you blend up a day’s worth of Chipotle and Muscle Milk and dye it tan as a control?)

I would certainly do a DEXA scan or Bod Pod before and after, not just BIA and a home scale. (Couldn’t help it this time with the broken table at one location and summer break at the other. Also, how does the entire city of Manhattan only have one of each of these?!)

To better measure muscle gain or loss, I would physically measure the inches of my waist, arms, chest, legs, and neck before and after.

Finally, to really make things interesting, I would love to split test subjects living off of various other meal replacements (they’re out there). The Ultimate Meal, GNC’s Lean Shake, Slim Fast, Naturade—shoot, even Muscle Milk (if I drank 4 of my 34g shakes a day, I’d get 100% of nearly all my vitamins and tons of protein).

While we’re at it, we might as well put the test subjects all in a house together and let MTV film.

Conclusions

After looking over the data and my daily observational journals, it appears that a Soylent diet contains more nutrition than my typical diet, and that I was able to absorb said nutrition sufficiently well. Even though I’m not in the habit of putting many bad substances in my body (except for caffeinated soda, which I have now cut off), I was definitely getting more balance and less junk via Soylent than I do with my normal routine. My blood tests show that I remained healthy under a Soylent regimen. I had no weird heart rate or sleep issues (and in fact seem to have slept better than normal), and I was indeed more alert.

However, the composition of my weight loss (3 lbs of fat and 1.2 lbs of muscle shed) indicates that I wasn’t getting enough protein to maintain lean muscle, given my height/weight and the 3-mile runs and pullups/pushups I do 3x a week. This speaks to the challenges of creating a one-size-fits-all formula in a food replacement. When I try Soylent again in the Fall, once the company ships orders, I plan to supplement with extra protein. Of course, Rhinehart and team are still tweaking the formula. They say they will soon release different flavors, and Rhinehart indicated to me that they could adjust the mixture for athletes. So more optimal protein/carb mixtures are likely in the cards at some point.

Going along with some of the skeptics I mentioned earlier, I do question the high amount of carbs and the use of oat flour and maltodextrin in the Soylent 0.8 formula; why not something healthier to deliver energy, like quinoa? Perhaps it’s a cost issue?

One thing to note is that these guys aren’t marketing Soylent as a fat-shredding regimen. It’s meant to be a health simplification diet. And that it absolutely was. Shockingly, so, I might add, because I expected to be miserable the whole time and was in fact quite happy. Beyond the time savings (and not having to think about food much), I was struck by how much easier it was to stick to a diet as simple as Soylent versus any other diet I’ve tried. As they say, it’s easier to be 100% obedient to a diet than 99%. Soylent left no room for debate, and therefore turned out to be quite easy.

(Though sticking to the diet was surprisingly easy, I did have one gripe: Nalgene bottles are a rather bad user experience with anything but water. The mouth of the bottle is huge, making it easy to spill. And spilled Soylent dries like paper mache.)

By far, the most interesting result to me was the cost and time savings of living on Soylent. I saved $200 during my trial. This is good news for the company’s greater mission of combating world hunger—especially since I imagine they’ll be able to manufacture and ship the stuff to impoverished areas at much cheaper than the kickstarter price. (One side note: the use of Soylent requires access to clean water, so there will be additional logistical challenges to making a “cure-all” for the world’s starving.)

My two weeks of Soylent is just a data point among a flood of results that will come out as the powder hits the market this fall. Long-term, clinical trials are certainly going to go a long way to proving the stuff’s effectiveness and safety to a degree that will not leave nutritionists nervous. But in my limited data set, signs point in a positive direction for the Soylent crew.

On the other hand, food is delicious. Much more delicious than Soylent, even though Soylent isn’t awful.

“We’re definitely not trying to compete with the experience of your mom’s cooking,” Rhinehart tells me. “Our goal is to make food more like water.”

I found a new appreciation for good food after living on Soylent for two weeks. That first bite of Angelo’s Pizza on my first day off was a truly aesthetic experience.

But all the freedom to eat heavenly, post-experiment food didn’t prevent me from saving half a bottle of Soylent after the last day of my diet, just in case I needed a quick meal sometime.

It wasn’t long before I did.

Shane Snow is a technology journalist in New York City. He contributes regularly to Wired Magazine, Fast Company, Advertising Age, and more. Follow him on Twitter @shanesnow or on his LinkedIn Influencer blog at http://www.linkedin.com/influencer/7374576. And if you’re especially adventurous, subscribe to his private mailing list at http://eepurl.com/yJaEP

Open Questions:

I came away from my Soylent experiment with a few unanswered questions. I’d love any insights or opinions from Tim’s readers on the following:

1) How much of a problem are the so-called “nutritionally empty” ingredients like Maltodextrin? Are carbs from that source (or oat flour) just as good as other carbs, so long as one gets all the other vitamins and minerals from other sources?

2) What powder-izable ingredients might one swap in for any of the Soylent ingredients to further optimize the formula?

3) What other variables ought to be controlled for in future experiments with Soylent?

4) What’s the probable explanation for the acid reflux and canker sores in the first few days? Is it possible that they were related to Soylent, or more likely related to other factors in my life?

5) Also, can we suggest some more marketable names than Soylent? (Or is the fact that it’s a hoax-sounding name good for marketing?)

Afterword from Tim

I commend the Soylent team for attempting to simplify food. The problems of nutrition and world hunger are worth tackling.

That said, I’d be remiss if I didn’t highlight a few points, voice a few concerns, and pose a few questions. Soylent has done an incredible job of building an international PR platform, sparked from single well-done blog post written before it was a business.

And with great audience comes great responsibility.

Food isn’t a game, and people can die. I propose that — if Soylent doesn’t modify it’s claims — people will die. For their customers and investors to remain intact, allow me to highlight a few things:

- Meal-replacement powders aren’t new. The only reason SF-based investors think it’s new it because of a novel target market: time-starved techies. Met-Rx pioneered meal-replacement powders (MRP’s) in the 1990′s, and there have been dozens of copycats since. From the Wikipedia entry:

Created by Dr. A Scott Connelly, an anesthesiologist, the original MET-Rx product was intended to help prevent critically ill patients from losing muscle mass. Connelly’s product was marketed in cooperation with Bill Phillips and the two began marketing to the bodybuilding and athletic communities, launching sales from the low hundreds of thousands to over $100 million annually. Connelly sold all interest in the company to Rexall Sundown for $108 million in 2000. MET-Rx is currently owned by NBTY.

- Be careful with any terminology like “FDA-approved” or indirect implications of medical-like claims. Get a good regulatory affairs law firm familiar with both compliance and litigation. Consumables at scale involve lawsuits.

- It’s premature to believe we can itemize a finite list of what the human body needs. To quote N.N. Taleb, this is “epistemic arrogance.” Sailors only need protein and potatoes? Oops, didn’t know about scurvy and vitamin C. We need fat-soluble vitamins? Oops, consumers get vitamin A or D poisoning, as it’s stored in body fat.

But let’s put aside a complex system like the human body–what about an isolated minimally-viable cell? Craig Venter, who sequenced the human genome, was recently interviewed by Bloomberg Businessweek on his team’s attempts to build one:

We’re trying to design a basic life form–the minimal criteria for life. It’s very hard to do it because roughly 10 percent of the genes are of completely unknown function. All we know is if we take them out of the cell, the cell dies. So we’re dealing with the limitations of biology.

Upshot: The human body isn’t well understood at all.

This doesn’t mean you can’t attempt to create good nutritional products; it does mean you need to mind your claims.

- Nutrition and people are not one-size-fits-all. Among the Soylent claims Shane outlined, there are the below. I’ve added my comments:

Soylent provides all the energy and nutrients the body needs.

[TIM: I'm not convinced Soylent can prove this.]

The body can absorb all the nutrients Soylent provides.

[TIM: I'm not convinced Soylent can prove this for healthy, normal subjects, let alone -- for instance -- people with celiac disease who cannot handle grains.]

Soylent makes one more alert.

[TIM: If measured, this could potentially be demonstrated.]

Soylent can help people cut fat and maintain good body weight.

[TIM: Be wary of any structure or function claims. Reword.]

Soylent saves time and money.

[TIM: Provable compared to another defined group (e.g. eating at Chipotle), but not across the board.]

And at the end of the day: Soylent isn’t dangerous.

[TIM: I'm not convinced Soylent can prove this. Where are the data? Safe for how long?]

I think claiming to know all the nutrients human’s require is dangerous. Claiming something is “safe” as opposed to a more objective/provable “all ingredients are on the GRAS list” is also playing with fire.

Given your early adopters, there’s a good chance you’ll have at least a handful of Type-I and Type-II diabetics (among other medical conditions) who are engineers prone to enjoying extremes. How do manage that with your user directions and messaging? What if they’re 100 pounds instead of 180? Or 350 pounds instead of 180? Don’t expect “Don’t use Soylent if you have a pre-existing medical condition” to stop them from using it exclusively as food, if that’s your positioning.

Tread carefully. Moderate claims are nothing to be ashamed of and can be monetized incredibly well. Don’t roll the dice with your customers’ long-term health.

Best of luck. I really hope you guys figure it out.

###

And dear readers, what do you think of Soylent’s approach and the above experiment?

Please join the conversation in the comments below. There several MDs, nurses, and nutritionists kindly offering their professional opinions (and answering questions).

Well, shit. I’ve been watching this situation for a few years, and assuming it would just blow over so we wouldn’t have to talk about it here in this place where we are supposed to be busy improving our lives.

Well, shit. I’ve been watching this situation for a few years, and assuming it would just blow over so we wouldn’t have to talk about it here in this place where we are supposed to be busy improving our lives.